2016-28 Noble Nature: "The Beaver and His Works" by Enos A Mills

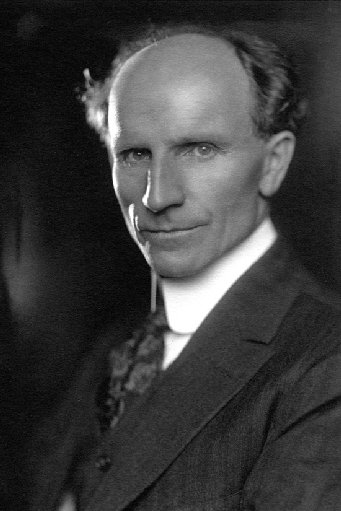

Enos A Mills [1870-1922] and John Muir [1838-1914]

|

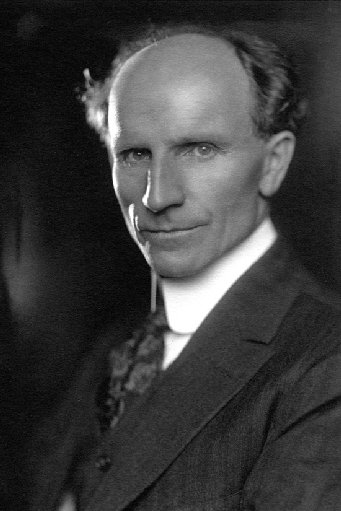

| John Muir [1838-1914] of the Mountains |

|

| Enos A Mills [1870-1922] |

Mills met Muir when Mills was a youth and Muir

was already an elder statesman.

Calling himself "the John Muir of the Rockies," Mills

said, "I owe everything to Muir. If it hadn't been for him I would have

been a mere gypsy."

He dedicated his book Wild Life on the Rockies [1909] to

John Muir where he wrote: "The peculiar charm and fascination that trees

exert over many people I had always felt from childhood, but it was John Muir,

who first showed me how and where to learn their language."

In his book, Your

National Parks [1917], Mills included a chapter about John Muir, in which he wrote,

"He had the poetic appreciation of Nature. He was the greatest genius

that ever with words interpreted the outdoors. No one has ever written of

Nature's realm with greater enthusiasm or charm.... He has written the great

drama of the outdoors. On Nature's scenic stage he gave the wild

life local habitation and character and did with the wild folk what Shakespeare

did with man.

His prose poems illuminate the forest, the

storm, and all the fields of life. He sings of sun-tipped peaks and gloomy

canyons, flowery fields and wooded wilds. He has immortalized the Big Trees.

His memory is destined to be ever associated with the silent places, with the

bird-songs, with wild flowers, with the great glaciers, with snowy peaks, with

dark forests, with sunlight and shadow, with the splendid National Parks, and

with every song that Nature sings in the wild gardens of the world.

"The Beaver and his Works" by Enos A Mills

[From Chapter 3 of "Wild Life on the Rockies" by Mills]

|

| Beaver - useful, thrifty, busy, skillful and picturesque |

I [Enos A Mills] have never been able to decide which I love

best, birds or trees, but as these are really comrades it does not matter, for

they can take first place together. But when it comes to second place in my

affection for wild things, this, I am sure, is filled by the beaver. The beaver

has so many interesting ways, and is altogether so useful, so thrifty, so busy,

so skillful, and so picturesque, that I believe his life and his deeds deserve

a larger place in literature and a better place in our hearts.

|

| Beavers' Engineering Works - Governing the Rivers and Fixing the Soil |

His [Beaver's] engineering

works are of great value to man. They not only help to distribute the waters

and beneficially control the flow of the streams, but also catch and save

from loss enormous quantities of the earth's best plant-food. In helping to do

these two things,—governing the rivers and fixing the soil,—he plays an

important part, and if he and the forest had their way with the water-supply,

floods would be prevented, streams would never run dry, and a comparatively even

flow of water would be maintained in the rivers every day of the year.

A number of beavers establishing a colony made

one of the most interesting exhibitions of constructive work that I have ever

watched. The work went on for several weeks, and I spent hours and days in

observing operations.

|

| Beaver cutting a tree |

While cutting, the beaver sat upright and

clasped the willow with fore paws or put his hands against the tree, usually

tilting his head to one side. The average diameter of the trees cut was about

four inches, and a tree of this size was cut down quickly and without a pause.

When the tree was almost cut off, the cutter

usually thumped with his tail, at which signal all other cutters near by

scampered away. But this warning signal was not always given, and in one

instance an unwarned cutter had a narrow escape from a tree falling perilously

close to him.

Once a large tree is on the ground, the limbs

are trimmed off and the trunk is cut into sections sufficiently small to be

dragged, rolled, or pushed to the water, where transportation is easy.

As workers, young beavers appear at their

best and liveliest when taking a limb from the hillside

to the house in the pond. A young beaver will catch a limb by one end in his

teeth, and, throwing it over his shoulder in the attitude of a puppy racing

with a rope or a rag, make off to the pond. Once in the water, he throws up his

head and swims to the house or the dam with the limb held trailing out over his

back.

|

| Drawing of a typical Beaver House |

The typical beaver-house seen in the Rockies at

the present time stands in the upper edge of the pond which the beaver-dam has

made, near where the brook enters it. Its foundation is about eight feet

across, and it stands from five to ten feet in height, a rude cone in form.

Most houses are made of sticks and mud, and are apparently put up with little

thought for the living-room, which is later dug or gnawed from the interior.

The entrance to the house is below water-level, and commonly on the bottom of

the lake. Late each autumn, the house is plastered on the outside with mud, and

I am inclined to believe that this plaster is not so much to increase the

warmth of the house as to give it, when the mud is frozen, a strong protective

armor, an armor which will prevent the winter enemies of the beaver

from breaking into the house.

Each autumn beavers pile up near by the house, a

large brush-heap of green trunks and limbs, mostly of aspen, willow,

cottonwood, or alder. This is their granary, and during the winter they feed

upon the green bark, supplementing this with the roots of water-plants, which

they drag from the bottom of the pond.

Along in May five baby beavers appear, and a little

later these explore the pond and race, wrestle, and splash water in it as

merrily as boys. Occasionally they sun themselves on a fallen log, or play

together there, trying to push one another off into the water. Often they play

in the canals that lead between ponds or from them, or on the

"slides." Toward the close of summer, they have their lessons in

cutting and dam-building.

As soon as the beaver's brush dam is completed,

it begins to accumulate trash and mud. In a little while, usually, it is

covered with a mass of soil, shrubs of willow begin to grow upon it, and after

a few years it is a strong, earthy, willow-covered dam. The dams vary in length

from a few feet to several hundred feet. I measured one on the South Platte

River that was eleven hundred feet long.

|

| Highway for the Folk of the Wild |

The influence of a beaver-dam is astounding. As

soon as completed, it becomes a highway for the folk of the wild. It is used

day and night. Mice and porcupines, bears and rabbits, lions and wolves, make a

bridge of it. From it, in the evening, the graceful deer cast their reflections

in the quiet pond. Over it dash pursuer and pursued; and on it take place

battles and courtships. It is often torn by hoof and claw of animals locked in

death-struggles, and often, very often, it is stained with blood. Many a drama,

picturesque, fierce, and wild, is staged upon a beaver-dam.

An interesting and valuable book could be

written concerning the earth as modified and benefited

by beaver action, and I have long thought that the beaver deserved at least a

chapter in Marsh's masterly book, "The Earth as modified by Human

Action." To "work like a beaver" is an almost universal

expression for energetic persistence, but who realizes that the beaver has

accomplished anything? Almost unread of and unknown are his monumental works.

Only a few beavers remain, and though much of

their work will endure to serve mankind, in many places their old work is gone

or is going to ruin for the want of attention. We are paying dearly for the

thoughtless and almost complete destruction of this animal. A live beaver is

far more valuable to us than a dead one. Soil is eroding away, river-channels

are filling, and most of the streams in the United States fluctuate between

flood and low water.

|

| We need to cooperate with the Beaver |

A beaver colony at the source of every stream would

moderate these extremes and add to the picturesqueness and beauty of many

scenes that are now growing ugly with erosion. We need to coöperate with the

beaver. He would assist the work of reclamation, and be of great service in

maintaining the deep-waterways. I trust he will be assisted in colonizing our

National Forests, and allowed to cut timber there without a permit.

The beaver is the Abou-ben-Adhem of the wild.

May his tribe increase.

For a Biographical Portrait of Enos A Mills: [Click Here]

|

| Enos A. Mills [1870-1922] |